Of the eight national parties in India as of now, four have a history of splits (Congress, Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) and the two Communist parties). One of the national parties (BSP) has a symbol, elephant, that continues to confuse voters beyond Uttar Pradesh while the last entrant to the league, National People’s Party (NPP) from Meghalaya in 2019, has ‘book’ as its symbol; only the BJP can lay claim to uninterrupted continuity of its name and its election symbol, the lotus. Do election symbols matter? With increasing penetration of mobile phones, TV and social media besides increased literacy, it is argued that awareness of symbols can spread faster; and that they are no longer are as important as they once were.

But both factions of the Shiv Sena will disagree, having laid their claim to the bow and arrow, the symbol reserved for the party since its inception. Along with party colours and the flag, the symbol is what gives them an identity, they believe. The Election Commission has frozen the reserved symbol of Shiv Sena–bow and arrow– and temporarily allotted the ‘mashaal’ to the Uddhav Thackeray faction and ‘a shield with two swords’ to the Shinde faction Party symbols were initially introduced to familiarise voters with multiple political parties.

With over 2,000 registered but unrecognised political parties, even after the recent purge for inactivity, besides the recognised state parties and national parties (see box), symbols even today have traction with voters pointing to haathi (elephant), haath (hand), cycle (bicycle) or kamal (lotus) to show their preference. After the Congress split in 1969, the old guard—who had thought Indira Gandhi would be malleable, labelling her a ‘goongi gudiya’ (dumb doll)—expelled her from the party; she retaliated by walking away with her supporters. They called themselves by the confounding name of Congress (Requisitionists) with which voters were unlikely to identify themselves.

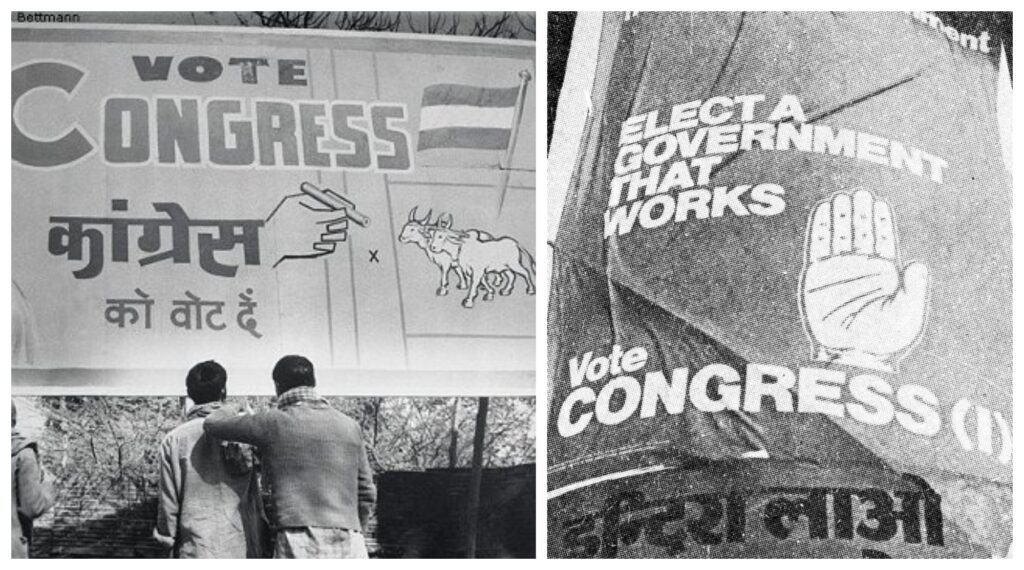

The ‘Old Guard’ asserted that it was the original Congress and the Election Commission allotted the then Congress symbol of a ‘farmer with bullock’ to Congress (O). Mrs. Gandhi had the choice of the cow with a suckling calf which, never mind the R in Congress(R), was suitably rural for the vast population of farmers who voted for the party.

Mrs Gandhi won all the subsequent by-polls and in 1971 came back with a sweeping victory on that symbol and the Garibi Hatao slogan. By 1975, most of the old guard in the Congress(O) had disappeared into oblivion or joined the Congress(R). The next split in 1978 gave Mrs.

Gandhi some sleepless nights over her new symbol. There was such acrimony in the party over their post-Emergency defeat and so much noise over the cow and calf imagery that the EC froze that symbol—along with the original farmer and bullock—forever. There was little in the EC’s list of symbols that was representative of the Congress’s roots among the poor and farmers.

After much deliberation with advisors, she rather unhappily chose the symbol of the ‘Hand’, recalled Najma Heptulla, now with the BJP. It was meant to convey blessings but Mrs. Gandhi was not quite sure if the upturned hand would be considered presumptuous and arrogant.

Najma Heptulla, a niece of Maulana Azad, was one of those Mumbai Congress leaders then who had stood by Mrs. Gandhi when she was in the wilderness post-Emergency. Heptulla once claimed to this writer that at a luncheon the discussion was if the ‘Hand’ symbol would be advantageous or damaging to the new faction called the Congress (I)—no one was quite sure if the ‘I’ stood for Indira or India.

Heptulla’s youngest daughter, then barely out of kindergarten, suddenly piped up to say, “Gai? Haath se toh aap gai ka doodh bhi nikaal sakte hain!” (Cow? But you can milk the cow with the hand!”). That baby-talk, Heptulla said, helped Mrs. Gandhi make up her mind and accept the symbol for her party.

Two decades later, Congress faced another split engineered by Sharad Pawar, who believed he could convince the people he represented the real Congress. He decided to name his party Indian Nationalist Congress. But the Election Commission asked Pawar to find a more distinctive name to differentiate it from the Indian National Congress and also denied Pawar his desired symbol of the chakra or the charkha.

Pawar had to settle for the alarm clock as the symbol and rename his outfit as Nationalist Congress Party. When the Communist Party of India split into two in 1964, the original symbol of the farmer with the plough (without a bullock) was frozen but both parties came up with their versions of the communist symbol, the sickle and the hammer. The CPI symbol had a lush ear of corn pushing through the half circle of the sickle while CPM stuck to the sickle and hammer with a red star above.

Apparently there has never been any confusion among Left voters. When the Congress and NCP allied with three factions of the Republican Party of India in 2004, they were in for a shock. The elephant had been the symbol allotted to B.

R. Ambedkar’s party. But when the Republican Party of India split into multiple factions (at last count 13) with as many leaders, the symbol was taken away and later allotted to the Bahujan Samaj Party.

But the older Dalit voters in Maharashtra continued to associate the elephant with the RPI, thus robbing Congress-NCP substantial number of votes which were unwittingly cast in favour of the BSP and not the RPI. The two parties undertook an awareness campaign for the “elephant voters” and later insisted that RPI candidates contest on either the Congress or the NCP symbol. In 2017 when Samajwadi Party faced a split in the family, with Shivpal Yadav claiming that the party was with him, the Election Commission decided that Samajwadi Party headed by Akhilesh Yadav had the support of legislators, MPs and office bearers.

The ‘bicycle’ symbol remained with him. .

From: nationalheraldindia

URL: https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/india/the-emotional-connect-of-election-symbols