Around the beginning of 2015, a Canadian tech entrepreneur from the small city of Trois-Rivières in Quebec—I’ll call him Paul Desjardins—was planning a trip to Thailand. A friend recommended that during his stay he meet up with a contact from their hometown who now lived in Bangkok. The man’s name was Alexandre Cazes.

Desjardins decided to pay him a visit. Cazes, he found, lived in an unremarkable, midsize house in a gated community in the Thai capital, but the baby-faced Canadian in his early twenties seemed to be doing well for himself. He had invested early in Bitcoin , he told Desjardins, and it had paid off.

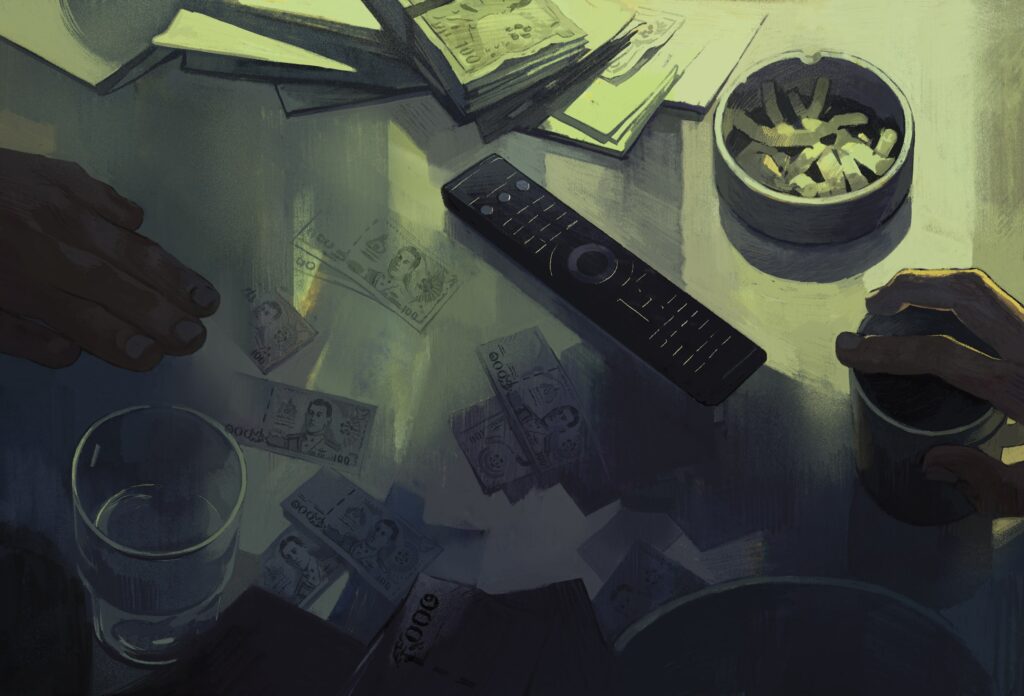

His biggest financial problem seemed to be that he now had more cash than he could deal with. He alluded to having sold bitcoins to Russian mafia contacts in Bangkok. A foreigner depositing the resulting voluminous bundles of Thai baht at a bank would raise red flags with local regulators, he worried.

So instead he had piles of bills accumulating around his home, even hidden in recesses in the walls. “There was money everywhere,” Desjardins remembers. “You open a drawer, and you find money.

” This story is excerpted from the forthcoming book Tracers in the Dark: The Global Hunt for the Crime Lords of Cryptocurrency , available November 15, 2022, from Doubleday. Despite Cazes’ liquidity issues and his somewhat alarming mention of the Russian mob, Desjardins couldn’t see any evidence that his strange new acquaintance was involved in anything overtly criminal. He didn’t use any drugs; he seemed to barely drink beer.

Cazes was friendly and intelligent, if socially strange and emotionally “very cold,” like someone going through the motions of human interaction rather than doing so naturally. “It was all logic,” Desjardins says, “ones and zeros. ” He did note that his new friend, while otherwise generous and good-natured, had ideas about women and sex that struck him as very conservative, bordering on misogynistic.

During that first visit, the two men discussed Desjardins’ idea for a new ecommerce website. Cazes appeared interested, and Desjardins suggested they work on it together. Back in Quebec around Christmas of that year, Cazes met with Desjardins again, this time to hear a full business pitch.

After no more than 15 minutes of discussion, Cazes was in. He impressed Desjardins by spending $150,000 without hesitation on a web domain for their business, not even bothering to haggle with the seller. In another pleasant surprise, Cazes also paid a six-figure legal bill that Desjardins had racked up in a dispute with another business.

He turned out to be a coding savant too; Desjardins had planned to hire a team of coders, but Cazes quickly did most of the initial programming for their fledgling site single-handedly. As they worked to get their business off the ground, Desjardins could see that Cazes was richer than he had first estimated. Desjardins learned that his partner was in the process of buying a villa in Cyprus and making some sort of real estate investment in Antigua.

When Desjardins next visited Bangkok, Cazes picked him up at the airport in a dark gray Lamborghini Aventador. Desjardins pointed out that there was nowhere in the supercar to fit his large suitcase. Cazes told him to get in anyway and gamely struggled with the luggage until it fit onto his guest’s lap.

Desjardins remembers seeing the suitcase scratch parts of the Lamborghini’s interior, but Cazes didn’t seem to care. In fact, he didn’t seem to have much emotional connection to the car at all; he didn’t even know how to use its radio. Desjardins thought Cazes appeared to own it out of a sense that it was the socially correct way to display his wealth.

As they left the airport, Cazes asked Desjardins whether he’d ever been in a Lamborghini before. He responded that he had not. Within seconds, Desjardins was flattened against the Aventador’s passenger seat as his eccentric friend rocketed them down the Bangkok highway at more than 150 miles per hour.

In late November 2016, just before Thanksgiving, Grant Rabenn was wrapping up his caseload in his office and preparing for the holiday when he got a call from Miller. “Hey, Grant,” Miller said. “I think I’ve got something big that we should talk about.

” They met at the Starbucks a block from Fresno’s courthouse. Miller explained what his tipster had told him: In AlphaBay’s earliest days online, long before it gained its hundreds of thousands of users or came under the microscope of law enforcement, the market’s creator had made a critical, almost laughable security mistake. Everyone who registered on the site’s forums at the time had received a welcome email, sent via the site’s Tor-protected server.

But due to a misconfiguration in the server’s setup, the message’s metadata plainly revealed the email address of the person who sent it—Pimp_alex_91@hotmail. com—along with the IP address of the server, which placed it in the Netherlands. The error had quickly been fixed, but only after the tipster had registered and received the welcome email.

The source had kept it archived for two years as AlphaBay grew into the biggest dark-web market in history. And now they had given it to Miller. It seemed that even the figure Rabenn once thought of as “the Michael Jordan of the dark web” was capable of elementary security errors—with permanent consequences.

Rabenn received Miller’s revelation coolly. He’d heard before from overexcited agents whose incredible leads led to dead ends or hoaxes. Surely, he thought, if his little team in Fresno had these clues, someone else in the US government must be miles ahead of them.

But they nonetheless decided to drop everything and follow the tip. There was, in fact, more to the source’s lead, all of which could be corroborated with a few Google searches. The Pimp_alex_91@hotmail.

com address also appeared on a French-language social media site, Skyrock. com. There, someone named “Alex” had posted photos of himself from 2008 and 2009, dressed in baggy shirts covered in images of dollar bills and jewels and wearing crisp new baseball caps with a silver pendant hanging from his neck.

In one picture he’d written his hip hop handle, “RAG MIND,” at the top of the image in the style of a debut rap album. The words on his shirt read “HUSTLE KING. ” A dating profile the man had posted to the site identified his hometown, Trois-Rivières in the French-Canadian province of Quebec, and his age at the time, 17.

So the “91” in his email address was his birth year. If this was indeed AlphaBay’s founder, he would have been 23 at the time of the market’s creation. Nothing about this young French-Canadian hip hop wannabe matched Rabenn and Miller’s sense of the kingpin known as Alpha02.

Had all of the allusions to Russia and Russian-language snippets been a ruse? Based on the IP address included in the tipster’s email, the site’s forums, at least, seemed to be based in Western Europe. To Miller and Rabenn, the theory that “Alex” was Alpha02 seemed outlandish at first. But the deeper they looked, the more plausible it became.

The young Quebecer had used his Pimp_alex_91 email address years earlier on a French-language technology forum called Comment Ça Marche—“How It Works. ” He had signed his messages with his full name: Alexandre Cazes. Searching for that name, the investigators came upon a more recent LinkedIn profile for a decidedly more adult Alex, sans hip hop outfit, advertising himself as a web programmer and the founder of a Quebec-based hosting and web design company called EBX Technologies.

His photo showed an unremarkable-looking businessman in a gray suit and white shirt with no tie. He had a round face with a cleft chin, slightly thinning hair in the front, and an innocent openness to his expression. Cazes listed his location as Quebec, Canada, but they could see from his social media connections that he seemed to actually be based in Thailand.

Further digging on social media revealed Facebook accounts for Cazes’ fiancée, a pretty Thai woman named Sunisa Thapsuwan. A telling photo on a relative’s profile showed Cazes in a suit and sunglasses, standing next to a dark gray Lamborghini Aventador. Digging deeper still, they found the most telling clues of all.

On Comment Ça Marche and another programming forum called Dream in Code were older profiles for Cazes that had been deleted, but they were preserved on the Internet Archive. Years earlier, it seemed, he had written on those forums under another username: Alpha02. Within days, Rabenn and Miller knew their lead was solid.

They also knew the case was too big for them to take on alone. They decided to bring their findings to the FBI field office in Sacramento, a much larger outpost just a few hours’ drive north with significantly more cybercrime expertise and resources than their small Fresno office. It turned out that the agents in Sacramento had been tracking AlphaBay from its inception.

Nonetheless, Miller’s tip was new information to them. Rabenn brought on the office’s assistant US attorney, Paul Hemesath, as an investigative partner. The two had been friendly for years; Hemesath, an older and more deliberate prosecutor, had the air of a college professor, and he balanced out Rabenn’s aggressive run-and-gun approach.

Hemesath in turn asked for help from the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section at Justice Department headquarters—the office in Washington, DC, where a small army of cybercrime-focused agents and computer forensics analysts was based. As they assembled their team, Miller and Rabenn began the delicate process of “deconfliction,” figuring out whether other agencies and task forces around the country had their own open cases on Alpha02. Again and again, Rabenn heard that another team in another city was investigating AlphaBay but had made no real headway.

None appeared to recognize the name Alexandre Cazes. Against all odds, Rabenn began to realize, his little office in the Central Valley was perhaps closer than anyone in the world to cracking the dark web’s deepest mystery. Soon they would find themselves at the vanguard of its biggest global manhunt.

If cazes had moved halfway around the world to Bangkok to run AlphaBay beyond the reach of Western law enforcement, he’d chosen, by some measures, exactly the wrong destination. For more than half a century, the US government has had an enormous presence in Thailand. Even before the DEA was founded in 1973, a US agency called the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs had stationed a field office in Bangkok.

American agents had long been sent there to disrupt the flow of so-called China White heroin from the opium-growing Golden Triangle region that covers parts of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar. In the late 1950s that triangle produced half of the world’s heroin supply and fed an epidemic of addicted US soldiers in Vietnam in the ’60s and ’70s—a problem that made quashing the Thai drug trade one of the DEA’s earliest and highest priorities. Fifty years later, Bangkok remains one of the largest and most active DEA offices in the world, the regional headquarters for the entire East Asia operations of the US law enforcement agency that has more overseas agents than any other.

For Jen Sanchez, it was also a plum assignment: beautiful weather, low cost of living, incredible food, and not particularly dangerous—relative to other DEA hot spots, anyway. Sanchez, a 26-year veteran of the DEA in her mid-fifties with white hair cut to her shoulders and a zero-bullshit, profanity-laden approach to conversation, felt she’d earned her coveted Bangkok job. She’d spent years in Mexico City investigating money laundering followed by a stint in Texas, where her work led to the arrest of three Mexican governors for taking bribes from the Zetas drug cartel and embezzling from their own state governments.

In that case, dubbed Operation Politico Junction, she’d tracked the governors’ dirty money into the businesses they’d bought to launder it, along with mansions, luxury cars, and private aircraft. In total, Sanchez had signed affidavits for seized assets worth more than $90 million. She’d come to relish the righteous thrill of bankrupting criminals who had spent their lives amassing ill-gotten wealth.

And since much of that money ended up in DEA coffers, it hadn’t exactly hurt her career, either. As she modestly put it, “I paid for myself. ” By December 2016, Sanchez had been in Thailand for nine months, mostly helping to track the financing for violent Islamic movements in the country’s south.

Then one day, at the Bangkok DEA office—situated in the US embassy, a white stone building with a canal surrounding its foundation and a grass lawn where 6-foot-long monitor lizards emerged from the foliage in the evening—her boss told her they had a visitor: a DEA official who was set to give them a presentation on virtual currency . Sanchez didn’t know anything about virtual currency. Nor, with just a few years left until retirement, did she particularly care to learn about it.

But she listened politely throughout the presentation. Only at the end of the session did the visiting agent truly get her attention: He mentioned, almost in passing, that the DEA had recently found a lead on the administrator of the world’s biggest dark-web market and that he seemed to be right there in Thailand. Sanchez had heard of Silk Road.

She asked whether this site was as big as that legendary black market. The agent responded that it was at least three or four times the size of Silk Road, and growing. “Holy shit,” Sanchez thought to herself.

The biggest dark-web kingpin in history was in her backyard? The scale of the money laundering alone would be enormous. “He’s going to have stuff ,” she remembers thinking. And she wanted to be the one to track down those assets and seize them.

Another group of agents in Bangkok had been assigned to handle the AlphaBay case. Sanchez’s own supervisor, to her constant frustration, seemed more interested in busting small-time dealers on the tourist beaches of Pattaya than in big-game, long-term investigations. But Sanchez was not about to be left out of what she suspected might be one of the largest seizures of cash and property—virtual or otherwise—in the history of the DEA in Thailand.

As soon as the presentation was over and the visiting agent left, Sanchez walked into her boss’s office, pointed a finger at him, and told him she wanted AlphaBay. Sanchez got her wish. She soon found herself on a series of sometimes bewildering conference calls among all the different agencies now hunting Cazes across a dozen time zones.

Those calls included Rabenn, Miller, Hemesath, and the Sacramento FBI team, who laid out AlphaBay’s basic mechanics and use of cryptocurrency. As Sanchez began to get a sense of the full extent of the massive commerce in hard drugs that AlphaBay now facilitated on a daily basis, she became incensed. The US opioid crisis was, by that time, in full swing; 42,000 Americans had died of opiate overdoses in 2016, more than in any year on record.

That surge was due in part to an influx of fentanyl, the opium derivative as much as 100 times stronger than morphine. And here this 25-year-old French-Canadian was running a massive open-air heroin and fentanyl bazaar in public view? She was haunted by the thought that every day AlphaBay was left online, anyone, even children, could order fentanyl from the site, receive it in the mail, and die of an overdose in a matter of hours. In one call with Miller in Fresno, she swore they would have AlphaBay offline and Cazes behind bars in less than six months.

“I’m going to take his shit, and he is going to go to jail, and we’re going to get him in Florence supermax,” she remembers telling Miller, referencing the prison where Ross Ulbricht was then serving his life sentence. “I want this kid gone. ” Now that Sanchez had joined the AlphaBay investigation, she was working under a new boss in Bangkok: a 47-year-old, Puerto Rico–born DEA agent named Wilfredo Guzman.

Guzman had started his career hunting drug-laden speedboats off the coast of Puerto Rico and had risen through the agency’s ranks following a series of massive Caribbean and South American cases. Now, as a supervisor in the Bangkok office, he prioritized, above all else, maintaining a hand-in-glove relationship with the Thai police’s DEA equivalent, known as the Narcotics Suppression Bureau (NSB). Doing so required near-constant late-night business dinners of painfully spicy food, drunken banquets, and karaoke outings, belting out John Denver lyrics onstage with high-ranking Bangkok cops.

The Royal Thai Police have a far-from-sterling record when it comes to drug trafficking and corruption. For some in the agency, shakedowns of petty drug dealers are understood to be a perk of the job. One RTP official named Thitisan Utthanaphon had earned the nickname Joe Ferrari for his collection of sports cars of mysterious provenance.

He would later be caught in a leaked video suffocating a suspected meth dealer to death alongside six fellow cops. So when Robert Miller asked Guzman in the agency’s Bangkok office for help in hunting Cazes, Guzman brought it to his most trusted contact at the NSB, Colonel Pisal Erb-Arb, who led the agency’s Bangkok Intelligence Center. Pisal was a spry, fatherly officer in his mid-fifties who frequently used his unassuming look as a balding middle-aged dad to take on undercover assignments.

He had assembled a small team known for its squeaky-clean, by-the-book investigative work, as well as for Pisal’s rare practice of advancing female agents. Almost immediately, Guzman, Pisal, and the NSB team got to work tracking down their new target. Starting with just Cazes’ name and a telephone number, they began to map out his properties: one home in a quiet gated community that he visited intermittently—what they came to call his “bachelor pad” or “safe house”—and another in his wife’s name in a gated neighborhood on the other side of town, where he seemed to work and sleep.

He had bought and was remodeling a third home, a $3 million mansion, farther on the outskirts of Bangkok. Soon the investigators were shadowing Cazes’ every move around the city. The Thais were particularly fascinated to discover his Lamborghini, a supercar that cost nearly $1 million, as well as his Porsche Panamera and BMW motorcycle, all of which he drove at speeds well above 100 miles an hour whenever Bangkok traffic allowed.

Following Cazes proved to be a moderate challenge: He frequently zoomed away from the agents tailing his sports cars on stretches of unbroken highway or lost them while snaking between trucks and tuk-tuks on his motorcycle. Pisal used a bit of personal tradecraft to plant a GPS tracker on Cazes’ Porsche, posing as a drunk and collapsing next to the car in a parking garage, then affixing the device to its undercarriage. The police tried attaching a similar tracking beacon to the Lamborghini but found that the car’s chassis rode so low to the ground that their gadget wouldn’t fit.

They resorted to tracking Cazes’ iPhone instead, triangulating its position from cellular towers. As Pisal’s team began to assemble a detailed picture of Cazes’ daily life, they were struck by how aboveboard it all seemed. He was a “homebody,” as one agent put it, spending entire days without stepping outside.

When he did leave his home during the day, he would go to the bank or his Thai language classes downtown, or take his wife out to restaurants or the mall. He lived, as Pisal put it using an English phrase commonly adopted by Thais, a “chill-chill” life of leisure. Could their too-good-to-be-true tip have been some sort of elaborate misdirection? Was someone just trying to frame Cazes, to use him as a patsy? It soon became apparent to Guzman and the Thai police that Cazes did have one very significant secret in his nondigital life: He was a womanizer.

He frequently ventured out in the evenings to pick up dates—from a 7-Eleven, from the mall, from his language class—and take them to his bachelor pad, or else to love motels. These encounters were businesslike and brief. By the end of the night, Cazes would be back at home with his wife.

So-called sexpats—foreigners using their wealth to live out polyamorous fantasies—were common in Thailand. And as scandalous as Cazes’ affairs might have been, there was no law against philandering. Still, the Thais needed little convincing that Cazes must be some form of crime boss.

At one point the surveillance team trailed him to a restaurant called Sirocco on the roof of Bangkok’s Lebua hotel; 63 floors up, it claimed to offer the highest alfresco dining in the world, with two Michelin stars and $2,400 bottles of wine on the menu. When Cazes and a group of friends left the restaurant, the cops entered and spoke to Sirocco’s management, demanding the entire day’s receipts to obscure whose bill they were hunting for. Including wine and lavish tips, they found that Cazes had spent no less than 1.

3 million baht—nearly $40,000—in a single meal for his entourage, an amount that flabbergasted even the agents accustomed to tracking high-rolling drug kingpins. Drug lords who never touched narcotics themselves or directly carried out crimes were nothing new to the NSB agents. They were used to the notion that the cleaner a suspect’s hands were, the more senior the position they likely held in a drug trafficking syndicate.

But those high-ranking bosses often met with associates who were connected to hands-on crimes or were at least a step or two removed from them. Cazes’ criminality, by contrast, seemed to be channeled entirely through the opaque aperture of the dark web, safely behind the veil of Bitcoin’s blockchain . In the physical world, his hands were cleaner than those of any kingpin they’d ever encountered.

At times, this perfect veneer led even the US investigators to doubt themselves. Sure, Cazes seemed to have slipped up once, years ago, when he left that Pimp_alex hotmail address in the metadata of a welcome email. But as their burgeoning investigative team followed up on that initial lead, Rabenn and Hemesath periodically asked each other whether they truly had the right guy.

Could their too-good-to-be-true tip have been some sort of elaborate misdirection? Could someone have purposefully leaked the address—and even chosen the handle Alpha02—as a way to frame this Cazes, to use him as a patsy? “The nightmare scenario would be that the source was setting us up,” Rabenn remembers thinking. The only way to know for sure, they would soon find, lay in a different approach—one that only a few years earlier would have seemed impossible. By early 2017, there was a new, growing class of investigators who saw Bitcoin’s blockchain as something other than an impenetrable veil.

They had come to realize that, far from a mysterious, anonymous currency, Bitcoin was, in fact, an almost entirely traceable financial system. And it was those tracers who would offer the next breakthrough in the race to take down Alpha02. By late 2016, a pair of FBI analysts, both based in Washington, DC, had gained a reputation as perhaps the very best team of cryptocurrency tracers in the US government.

(Per their request, they are referred to here by only their first names, Ali and Erin. ) The two shared a focus on digital money laundering, a fascination with cryptocurrency, and a yearslong friendship. Despite working for different investigative groups in different offices, they had come to form a two-person team of their own, practically mind-melding into two lobes of a single Bitcoin-obsessed brain.

And they operated almost entirely under the radar, only ever producing leads that they quietly handed off to other investigators, clues that appeared in no criminal affidavits or courtroom evidence. As it happened, on a winter morning just weeks after Robert Miller had received his Alpha02 tip—and before almost anyone else in the US government knew about it—Ali had come to Erin with an idea. She’d left the FBI satellite office where she worked, in a grim Beltway office park in Chantilly, Virginia, and driven for half an hour through DC traffic to ambush Erin at her desk at FBI headquarters.

Ali, the more ebullient and ambitious of the two, wanted Erin to push aside all their other work so they could try something no one had ever pulled off before: tracking down a dark-web administrator—perhaps even the admin of AlphaBay—through the techniques of blockchain analysis alone. Before Erin had time to protest, Ali squeezed a chair into Erin’s tiny cubicle and impatiently grabbed her mouse to start clicking through Bitcoin addresses on her computer screen. Ali’s ambition to expose a dark-web kingpin’s finances had come to seem attainable only after years of advances in crypto-tracing techniques—the latest of which had AlphaBay specifically in their crosshairs.

Ali and Erin were both fluent users by that point of Reactor, a piece of software made by a New York startup called Chainalysis . Together with a handful of other companies like it, Chainalysis had, since 2014, pioneered and automated a set of powerful new methods for tracing cryptocurrency. Those efforts had quietly flipped the criminal promise of Bitcoin on its head, rendering the blockchain into a branching series of breadcrumb trails that allowed cybercrime investigators to follow the money as never before.

Some of these techniques were relatively straightforward. For instance, a crypto tracer using Reactor could sometimes follow bitcoins as they moved from address to address until they reached one that could be tied to an account at an exchange, where they were cashed out for traditional currency. Then Chainalysis’ customers in law enforcement could simply subpoena the exchange for the account holder’s identity, since US law required exchanges to collect this information on American users.

Chainalysis’ more powerful contribution to bitcoin tracing had been a collection of “clustering” methods that allowed it to show when different Bitcoin addresses—dozens to millions of them—belonged to a single person or organization. If Reactor showed that coins from two or more addresses were spent in a single “multi-input” transaction, for example, that meant one entity must have control of all those addresses. This trick had made Silk Road users’ money relatively easy to track: Just send a few test transactions to any Silk Road account, and the market’s wallet system would soon bundle up your coins with others in multi-input transactions, leading to a cluster of other Silk Road addresses—like a briefcase full of bills with a homing device inside, brought back to a criminal’s hideout.

But Chainalysis had found that the same method didn’t work on AlphaBay, which seemed to carefully avoid pooling users’ payments, and kept them instead in many small, disconnected addresses. Indeed, by April 2016, AlphaBay had begun advertising to users that it functioned as a bitcoin tumbler: Put money into an AlphaBay account, and it purportedly severed any link that could be used to follow it from where it entered the market to where it left. “No level of blockchain analysis can prove your coins come from AlphaBay because we use our own obfuscation technology,” read one 2016 post from AlphaBay’s staff to users on the site.

“You now have ironclad plausible deniability with your bitcoins. ” Those claims, Chainalysis found, turned out to be largely true. Because AlphaBay never gathered coins into large, easily identifiable purses, it was nearly impossible to look at any given transaction on the Bitcoin blockchain and tell whether it involved a trade on AlphaBay.

That layer of obfuscation represented a serious problem for Chainalysis’ many customers in law enforcement. And so for much of 2016, mapping all the addresses on the blockchain that were associated with AlphaBay users—the dark market’s “wallet”—had become the most difficult and pressing challenge Chainalysis had ever taken on. Month after month, Chainalysis’ staff performed hundreds of test transactions with AlphaBay—never actually buying anything from the market, only moving money into and out of accounts—and watched the patterns those transactions formed on the blockchain, in hopes of finding clues that they could use to spot patterns elsewhere in the vast expanse of Bitcoin’s accounting ledger.

Gradually, the company’s researchers found distinct tells in the way AlphaBay moved its users’ money. These clues came from the highly specific choices made by Alpha02 and whoever else was writing the code of AlphaBay’s wallet. Chainalysis refused to divulge most of them, but cofounder Jonathan Levin offered an example.

According to the system of incentives devised by the currency’s creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, a Bitcoin wallet has to pay a fee for each transaction; the greater the fee, the more likely the thousands of servers known as Bitcoin nodes—the backbone of the Bitcoin network—are to quickly rebroadcast the transaction so that the entire network agrees that the transaction occurred. Most wallets allow users to set their own fees along a sliding scale of speed versus cost. Dark-web markets, however, typically set their own fees.

On AlphaBay, Chainalysis discovered, larger transactions required larger fees according to a distinct sliding scale. This represented a small tell—one of many, Levin says—that would allow them to spot transactions likely happening on AlphaBay and so produce a new set of addresses that would then, in turn, lead to others. It was painstaking work.

Every time AlphaBay rewrote the software for its wallet, the telltale patterns changed. Yet by the end of 2016, Chainalysis had labeled more than 2. 5 million addresses as part of AlphaBay’s wallet.

For Chainalysis’ law enforcement customers, however, that breakthrough was just a starting point. The task that still lay ahead would be to follow the money from somewhere in that vast pile of numbers out to the bank account of a real human being. And from a cubicle in Washington, DC, that’s exactly what Ali and Erin set out to do.

On that winter day in 2016 when Ali decided to conscript Erin into her unprecedented scheme, she hurriedly explained to Erin a realization she’d had. Dark-web markets, everyone knew by then, were notoriously vulnerable to “ exit scams ”: schemes in which an administrator suddenly shuts down a market and then absconds with all its users’ money. Every time this happened, dark-web forums were flooded with laments and reminders that no one should store any more cryptocurrency on a market than they planned to spend immediately.

But there was one person, Ali figured, who would never have to worry about an exit scam when considering where to keep their crypto savings: the dark-web site’s administrator himself. “Who would have the most faith to leave their money on the market?” Ali asked Erin. “Of course it would be the guy in charge.

” So what if they simply searched for the black market addresses that had held the largest sums of bitcoins for the longest time? The biggest, most stationary piles of money might just belong to the bosses. Erin admitted it was a good idea. But after identifying a few addresses to look at, she shooed Ali out of her office to get on with her other work.

After all, no one had asked them to track down Alpha02; they had intelligence reports to write and more realistic targets to hunt. The next day, however, Ali began calling Erin every few minutes with breathless updates. She had started with the address of the biggest sum of bitcoins that had sat unmoved for the longest time among all the wallet addresses tied to the AlphaBay cluster.

And, spotting the point where that money had finally changed addresses, she’d been able to track its movements from one hop to another, following its path in Reactor through the branching tendrils forking off from the market. “It’s still going!” she’d tell Erin excitedly on the phone as she followed it from one address to the next. Soon Erin, infected by Ali’s enthusiasm, was digging through other unmoved piles of bitcoins that she now suspected might be an administrator’s commissions.

Talking constantly on the phone across the DC–Virginia border, they began to devote hours to their Alpha02 hunt, scanning through hundreds of AlphaBay addresses in Reactor. Whoever owned these piles of presumably criminal money had, at least in some cases, taken pains to hide their footprints on the blockchain. The funds would sometimes flow into clusters of addresses created by services known as mixers, advertised on dark-web sites with names like Helix and Bitcoin Fog.

These bitcoin-laundering services offered to take in coins, pool them with other users’ funds, and then return all the coins in the pool to their senders at new addresses. In theory this would cut the forensic link for any tracer, like a bank robber who slips into a movie theater, takes off his ski mask, and walks out with the crowd, evading the police on his tail. Ali and Erin did sometimes hit dead ends in their work to trace Alpha02’s profits.

But in other cases, they were able to defeat his efforts at obfuscation. Neither of the two FBI analysts would reveal how they overcame Alpha02’s use of mixers, but crypto tracers like those at Chainalysis offered hints. A mixer, Jonathan Levin explained, is only as good as its “anonymity set”—the crowd of users mixing their coins to render them untraceable.

Despite whatever claims mixers made to their customers, examining their work on the blockchain revealed that many didn’t actually offer an anonymity set large enough to truly flummox an investigator. The more money someone tried to launder, the harder it became to avoid those coins remaining recognizable when they reappeared on the mixer’s other end. Any decent mixer splits large sums of coins into smaller, less conspicuous payments when returning the money to its owner.

But with transaction fees for every payment, there’s a limit to how much big sums of money will be broken up, Levin says. In truth, Chainalysis didn’t need to offer its users proof of the path that money took on the blockchain, so much as probability. Grant Rabenn candidly explained that the bar for sending a subpoena to a cryptocurrency exchange for a user’s identifying information was low enough that they could simply try multiple educated guesses.

All of this meant that, in spite of a criminal’s best efforts, investigators were often left with suspicious outputs from mixers, ones that they could follow with enough likelihood—if not certainty—of staying on their target’s trail. Even the crowded-movie-theater trick, it turns out, breaks down when the robber is carrying a large enough sack of loot and the cops are watching every exit. As Ali and Erin followed what they increasingly believed to be Alpha02’s personal transactions, they gave nicknames to the most significant Bitcoin addresses they were scrutinizing, turning the strings of meaningless characters into pronounceable words.

An address that started 1Lcyn4t would become, in their private language, “Lye sin fort. ” One that began with the characters 3MboAt would be pronounced “Em boat. ” The two analysts spent so much time examining and discussing these names that the addresses began to take on “personalities” in their minds.

(“It’s not exactly healthy,” Erin said. ) Of all of their named addresses, one loomed largest in the two analysts’ conversations. They refused to reveal even its nickname for fear that someone might reverse engineer the actual address and learn their tricks.

For the purposes of this story, let’s call it “Tunafish. ” Tunafish lay at the end of a long string of hops Ali and Erin had followed out from one of the initial addresses that they’d hypothesized might be Alpha02’s. It held special significance, however: It connected directly to an exchange.

For the first time, they realized with excitement, they had managed to trace what they suspected might be a collection of the AlphaBay admin’s bitcoins all the way to a transaction in which Alpha02 had traded them for traditional currency. They knew it was at those cash-out points—the blockchain’s connections to the brick-and-mortar world of finance—that they might be able to match the transactions to a real person. Just as they were on the verge of ferreting out a name behind all of Alpha02’s transactions, Ali got wind of some news quietly floating among law enforcement agents across the country.

As a longtime dark-web analyst, she’d kept in close contact for years with the Sacramento FBI agent who had first opened a file on AlphaBay. So when the Sacramento office joined forces with Grant Rabenn’s Fresno team, Ali was among the first people the agent called. He told her that they had finally matched a real person to Alpha02’s online persona.

He gave her the name of a certain French-Canadian living in Bangkok. Investigators started to recognize Cazes’ identifying tells. In some cases, his attempts to obscure his ownership of bitcoins became, themselves, a kind of fingerprint.

The Sacramento agent knew Ali was already busy tracing AlphaBay’s blockchain tentacles. He asked her to join their growing investigative team. Ali returned to Erin’s office at FBI headquarters, cornered her in the hallway, and insisted she join the team, too.

“This is going to be a massive case,” Ali told her. “We need to do this together. ” Erin said yes.

Now they were hunting Alpha02 no longer as an obsessive hobby, but as part of an official investigation. Ali and Erin explained their Tunafish discovery to an assistant US attorney based in DC who had also joined the team, a seasoned cybercrime prosecutor named Louisa Marion. She, Rabenn, and Hemesath immediately filed a subpoena for the identifying records on the exchange where the Tunafish address had been cashed out.

That legal request took weeks to bear fruit. Finally, one evening in the early weeks of January 2017, Ali was in the middle of a law school night class when she got a call from the Sacramento-based FBI agent with the news: The subpoena results had come back. The agent told her the name on the exchange account tied to the Tunafish address.

It was Alexandre Cazes. Over the next months, Ali and Erin continued to trace more high-value addresses out of the AlphaBay cluster into one cryptocurrency exchange after another. They came to recognize what seemed to be Cazes’ identifying tells, even in his bitcoin-laundering habits; in some cases, his attempts to obscure his ownership of the bitcoins became, themselves, a kind of fingerprint.

In total, the two analysts traced Cazes’ commissions to a dozen cryptocurrency exchanges. The prosecutors then subpoenaed these one by one, finding accounts registered in both Cazes’ and his wife’s names. And as those results came in, a yearslong pattern emerged: Cazes would open an account with an exchange and attempt to use it to cash out a chunk of AlphaBay’s profits.

At some point—often within months of his cash-out transactions—the exchange would grow suspicious about the origin of these massive cryptocurrency trades and ask for more know-your-customer information from him. Cazes would send a note explaining that he was merely an early investor in Bitcoin. In some cases the AlphaBay founder claimed to have bought thousands of coins from the defunct exchange Mt.

Gox in 2011 or 2012—knowing it would be difficult to check the records, given that Mt. Gox had declared bankruptcy in 2014. In others, Cazes claimed to have bought them from a private seller at the exchange rate of a dollar each.

“Since then, I’ve been pretty much juggling the coins like stocks, buying and selling, but never cashing out,” he wrote in one emailed explanation to an exchange. By 2017, however, legitimate Bitcoin businesses had learned to be wary of these unverifiable stories. In most cases they closed or froze Cazes’ account, forcing him to move onto another exchange.

Ali and Erin, meanwhile, could see the true source of Cazes’ wealth traced out in strand after strand of the blockchain’s connections. For years to come, the investigators involved in the AlphaBay case would debate whether their cryptocurrency tracing alone would have cracked the case even if they had never gotten the Pimp_alex_91 tip. Would the appearance of Cazes’ name on those exchange accounts have been enough to put them onto his trail, or would they have treated it as just another vague lead that they were too busy to chase down? Coming as it did, however, in the immediate wake of the tip sent to Miller about Alpha02, the two FBI analysts’ blockchain work nailed to the wall a theory that would have otherwise hung by only a few threads.

Every exchange subpoena and its results drew another line between Cazes and AlphaBay’s fortune. “When we saw millions of dollars in crypto flowing to him from what appeared to be AlphaBay-associated wallets, I was fairly confident that we had the right person,” Rabenn says. “When you hit that point, you start gearing up to indict.

” Continued next week : When investigators find Cazes’ online alter ego on a pickup artist forum, they also discover a new challenge to catching him red-handed—and hatch a plan for the most ambitious sting in dark-web history. This story is excerpted from the forthcoming book Tracers in the Dark: The Global Hunt for the Crime Lords of Cryptocurrency , available November 15, 2022, from Doubleday. If you buy something using links in our stories, we may earn a commission.

This helps support our journalism. Learn more . Chapter Illustrations: Reymundo Perez III Photo source: Getty Images This article appears in the November 2022 issue.

Subscribe now . Let us know what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor at mail@wired.

com . .

From: wired

URL: https://www.wired.com/story/alphabay-series-part-2-pimp-alex-91/