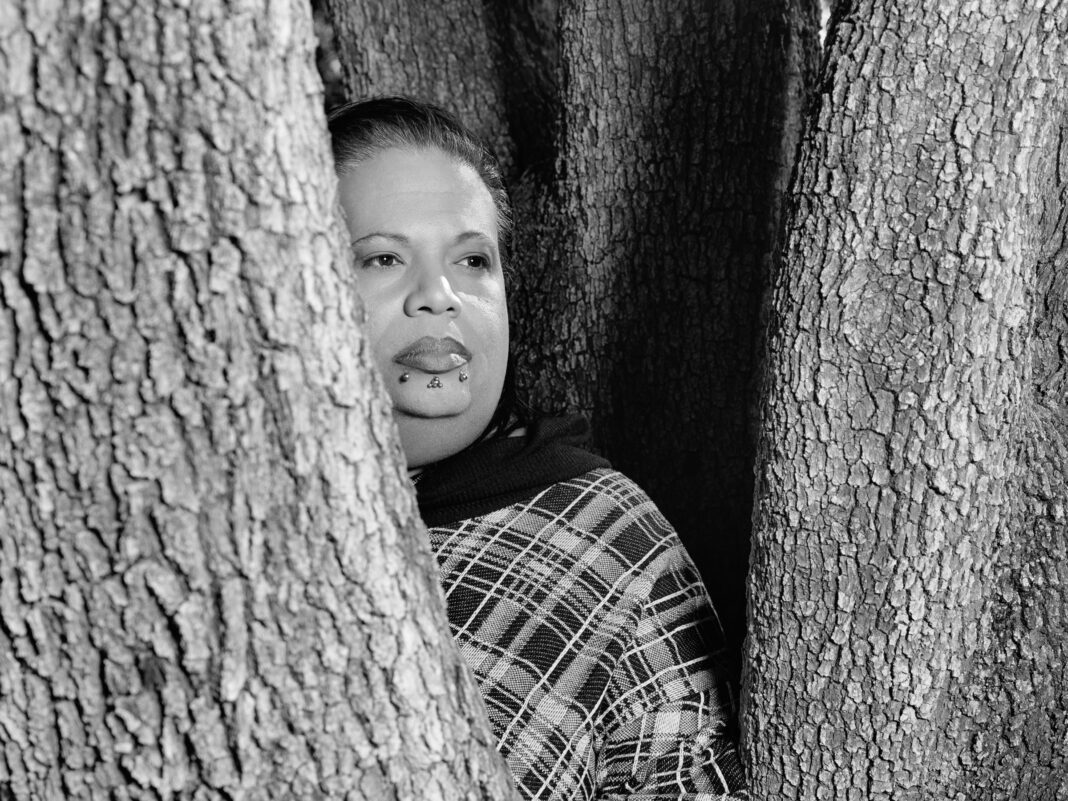

It’s been more than five years since an Uber self-driving car struck and killed a woman named Elaine Herzberg as she walked her bicycle across a road in Tempe, Arizona. Herzberg’s death instantly turned what had been a philosophical conundrum into a glaringly real, legal one: Who gets blamed for a road fatality in the awkward, liminal era of self-driving cars, when humans are essentially babysitters of imperfect, still-learning AI systems? Is it the company with the erring car? Or the person behind the wheel who should have intervened? On Friday, we got an answer: It’s the person sitting behind the wheel. In an Arizona courtroom, the test operator during the crash, Rafaela Vasquez, the subject of an in-depth WIRED feature last year , pleaded guilty to one count of endangerment and was sentenced to three years of supervised probation, with no time in prison.

In Arizona, endangerment is defined as “recklessly endangering another person with a substantial risk of imminent death or physical injury. ” In the Arizona case, the plea deal saves all parties from a trial’s uncertainty: If a jury had found Vasquez guilty of the original felony she was charged with—negligent homicide—she would have faced four to eight years in state prison. Vasquez told WIRED that prison was of particular concern to her as a transgender woman, given that she said she had suffered sexual abuse in the early aughts while incarcerated among males.

But the settlement also leaves unresolved Vasquez’s claim, made in legal filings, that she was not as off-task as prosecutors claimed. The case accused her of watching the talent show The Voice on her personal cell phone at the time of the crash, but she claims she was instead monitoring the company Slack on the handset she used for work. As for Uber, the plea saves the company from another embarrassing airing of its erstwhile self-driving program’s grave shortcomings, already highlighted in a lengthy investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board.

Vasquez’s legal team had shown every intention to make its defense about shifting blame to Uber, arguing that Vasquez had been set up to fail. (Uber didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment Friday. ) In pretrial filings, Vasquez’s attorneys cited the NTSB’s findings against Uber: The car failed to identify Herzberg as a pedestrian, and so failed to apply its brakes.

The NTSB also found that Uber kept an “inadequate safety culture,” doing little to protect test operators from the well-known phenomenon of “automation complacency”—humans’ tendency to direct less attention to automatic processes that demand little input. In the months before the crash, Uber had removed a requirement for there to be two test pilots in each car, which operators told WIRED had kept them more alert and adherent to the company’s no-cell-phone policy. Instead, in the months leading to the crash, solo operators were often looping the same monotonous route on hours-long shifts, left to self-police their usage of cell phones.

Uber forbade operators from using handsets while driving, but also had the operators keep the phones handy in the car in order to get company Slack messages. Several other test operators had been fired for violating the phone policy before the 2018 crash. Vasquez’s claim that she was monitoring Slack on her work phone came out in legal filings long after the NTSB published its report, which named her distraction as the “probable cause” of the crash.

Vasquez’s attorneys contend Vasquez was only listening to The Voice —as operators were allowed to do—and argue that the investigators mixed up which phone Vasquez was looking at in the seconds leading up to the fatality. As defense attorney Albert Morrison said in court Friday, “She was not watching The Voice , your honor. She was doing what she was asked to do by Uber, and that is to monitor the systems in the car.

Nonetheless, judge, she’s indicated that that conduct itself was reckless. She’s acknowledged that here today, and she’s accepting responsibility for that. ” While Vasquez and Uber may find some closure in the plea deal, self-driving expert Bryant Walker Smith says the NTSB should revisit the Slack issue to find the truth.

“I don’t want the story of the first automated vehicle fatality to be a lie. Or be a matter of disputes,” says Walker Smith, a law professor at the University of Southern Carolina. “We should get answers.

” Watching a show would suggest some culpability for Vasquez, he says; watching Slack raises questions about Uber’s policies and practices. The alleged problems with Uber’s self-driving car program were serious enough that a former operations manager of the self-driving-truck division, Robbie Miller, had written a whistleblower email to higher-ups in the days before the fatal Arizona crash, warning about the car division’s poor safety record and practices. After WIRED’s story on Vasquez published last year, Miller told WIRED that he hoped that Vasquez would take the case to trial, not settle.

(Miller is now chief safety officer at autonomous haulage company Pronto AI. ) “I hope she fights it,” Miller said at the time. “I do think she has some responsibility in this, but I really don’t think what they’re doing to her is right.

I think she was just put in a really bad situation where a lot of other people under the same set of circumstances would have made that mistake. ” According to Vasquez’s court filings, another former Uber employee, a technical program manager in the self-driving-car division, went so far as to call the Tempe police after the crash, saying that the company had ignored risks. Other employees who talked to WIRED were also uneasy that Vasquez stood to bear all the criminal blame.

(A year after the crash, Arizona prosecutors cleared Uber of criminal liability. ) Vasquez’s guilty plea joins a similar resolution this summer in Southern California, where a driver was criminally prosecuted for failing to take his Tesla out of Autopilot in a 2019 crash that resulted in two adults’ deaths—the first US prosecution of its kind. Kevin George Aziz Riad had his hand on the wheel, a Tesla rep had testified, as his Tesla ran a red light at 74 miles per hour and hit a car, killing two people inside.

In June he pleaded no contest to two felony counts of vehicular manslaughter and was sentenced to two years of probation, avoiding prison. Vasquez’s guilty plea lands in a summer rife with worry over the dangers of AI. California has become the site of a battle over whether Cruise’s and Waymo’s self-driving robotaxis can charge for full-time service to the public, with San Francisco officials arguing the tech isn’t yet ready or safe .

But as the self-driving advocates have long argued, the status quo isn’t exactly safe either: The industry’s mission is to remove human error from driving, which kills more than 40,000 people in the US each year. Arguably, the fault in the Tempe fatality was also all too human too: a combination of the human recklessness that went into Uber’s flawed test program and Vasquez’s failure to watch the road. Beyond the courtroom, Uber faced upheaval: The crash marked the beginning of the end of the company’s self-driving unit, which was eventually shuttered and offloaded .

Still, Uber bought a stake of the company that acquired its division, and Uber announced it will be offering Waymo cars on its ride-hailing platform in Arizona later this year, ensuring that the company will have a foothold in the self-driving future without developing a car itself. (“I’m not sure that’s a great story of remorse and consequence,” Walker Smith says. ) Herzberg is gone, and Vasquez has faced five years of legal purgatory alone, with three more years of probation still in front of her.

“It is disturbing to me,” Miller, the whistleblower, told WIRED of the prosecution of Vasquez. “It just seems like it’s easy to pin it on her. ”.

From: wired

URL: https://www.wired.com/story/ubers-fatal-self-driving-car-crash-saga-over-operator-avoids-prison/