Science 5 Management Lessons From An Apollo 13 Astronaut, Part 4: An Idea Is Not A Plan Elizabeth Howell Contributor Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own. I write about all things space — exploration, astronomy and more. New! Follow this author to improve your content experience.

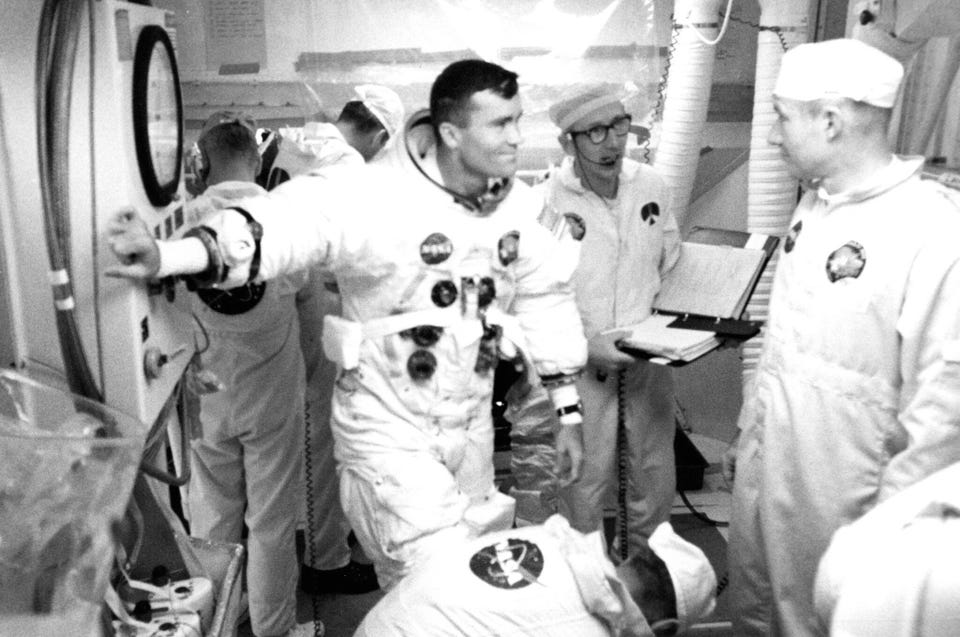

Got it! Jul 30, 2022, 11:02am EDT | New! Click on the conversation bubble to join the conversation Got it! Share to Facebook Share to Twitter Share to Linkedin NASA astronaut Fred Haise (in spacesuit) during flight preparations for Apollo 13. NASA One of the most iconic vehicles of the early space age was the lunar module, the Grumman (today’s Northrop Grumman) spacecraft that safely put six crews on the moon between 1969 and 1972. On Apollo 13, the lunar module Aquarius played an even more crucial function; the spacecraft, unharmed by a life-threatening problem that affected the main command module Odyssey, served as a lifeboat for the three astronauts suddenly redirected from their moon mission in 1970.

Aquarius got the group, including astronaut Fred Haise, back to Earth orbit for a re-entry in Odyssey. Haise continued with the agency as one of the pilots during space shuttle testing . After he left NASA, Haise was president of Grumman Technical Services, a subsidiary of Grumman.

Their duties included a launch processing system to support launches for the new space shuttle program, along with supplying instruments for ground systems, among other things. In this role, he found himself embedded in one of the big programs by NASA of the 1980s: space station Freedom. The occasion of Haise’s interview was the publication of his memoir, Never Panic Early , written with Bill Moore and available now from Penguin Random House.

In the coming days, we’ll share five lessons that he learned from that mission. The third lesson, how large teams solve critical problems, is available at this link . Artist’s conception of one of the designs of space station Freedom.

NASA/Tom Buzbee Space station Freedom is a complex story of project management that didn’t in the end, produce a working space station. As whole books have been written about why, we’ll look at the topic just from a high level here. The station as most people recognize it arose from plans under the Reagan administration, and was named Freedom in an announcement in July 1988.

The United States, Japan, Canada and nine European member states signed an intergovernmental agreement that September to build and use it for microgravity research. MORE FOR YOU New Research Finds A Connection Between Domestic Violence And These Two Personality Disorders This Scientist Helps Andean Forests And Ecuador’s Women In STEM Exceptional Fossil Preservation Suggests That Discovering Dinosaur DNA May Not Be Impossible One of the many reasons the station never made it was its ballooning cost relative to the available budget, despite numerous redesigns. (Another was the fall of the Soviet Union, which eventually led to the International Space Station as Russia was brought into a reconfigured space partnership.

) In his book, Haise describes the station as “my next adventure”, as Grumman was responsible for project management. Haise points to numerous problems that he encountered while working on Freedom, including “contentious” funding discussions in Congress, a hostile media, restructuring Grumman three times to deal with reduced funding, and changes in NASA management as high as the administrator (which saw three different individuals in quick succession, during Haise’s tenure. ) Internal management shifts at Grumman eventually moved Haise off the Freedom project, to his utter relief.

The International Space Station, which arose after Freedom was canceled. NASA There are numerous lessons that Freedom can show us, but for Haise one of the big ones was a lack of understanding of project management by some of the principal players. “When they said they have a plan, they really didn’t have an idea; it already failed,” he told Forbes.

A successful project, by contrast, “will have a work scope and requirements laid out to the scope of budgets, financial schedules. Sometimes you’ll even try to push it down to levels of work scope . ” As for cost, Haise said that while space projects can be complex and are known for going over budget, one of the responsibilities of the project manager is to estimate the finances within a “rough order of magnitude.

” Then as hiccups arise, as they inevitably will, you are able to use software programs to help manage the schedules, critical path and other elements for project success. For Part 5 of this series, we’ll cover the concept of growth and dealing with the unexpected. Follow me on Twitter .

Elizabeth Howell Editorial Standards Print Reprints & Permissions.

From: forbes

URL: https://www.forbes.com/sites/elizabethhowell1/2022/07/30/5-management-lessons-from-an-apollo-13-astronaut-part-4-an-idea-is-not-a-plan/