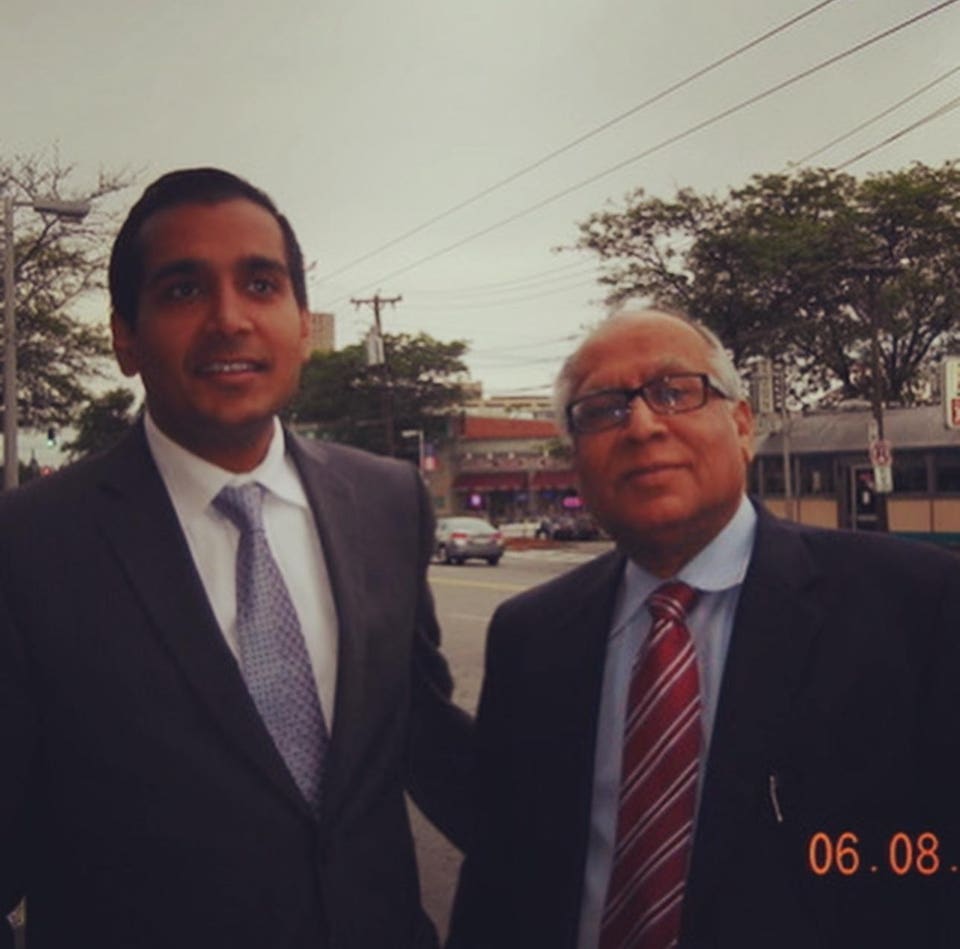

My father and I following my graduations from internal medicine residency at Brigham and Women’s Growing up in an Indian immigrant family in northern New Jersey, there was unstated expectation that I would pursue a career in medicine. So when I returned home from college my freshman year and announced that I might be interested in getting a law degree, my Dad—Dr. Subhash Jain, himself a physician—responded in his own inimitable way.

“I think going to law school is a great idea,” he told me. “ you go to medical school. ” (I later dropped the idea of law school for business school.

) Regardless of how I ended up in medicine and healthcare, I like to think that my parents—and my Dad, in particular—knew something about me that I didn’t know about myself. Because while I was unsure about a career in medicine at first, my clinical years at medical school were a time of inspiration when I felt deeply at home professionally. It was the right home for me.

My career in medicine was somewhat different from my father’s, but he played an outsized role in helping me develop my own perspectives as a physician and healthcare executive. My Dad started his career as the village doctor in Mandoli Nagar and Banswada, Rajasthan. He later immigrated to Canada and then moved to New York, where he pursued training in surgery, anesthesiology, and pain management.

He spent most of his career as an academic pain management physician and was the founding chief of the pain service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. For much of my life, Dad was the person I most sought to impress with whatever I was doing—but he was also a voice of reason and always tried to ground me in common-sense wisdom. I lost my Dad , but the lessons he taught me (and others) live on.

My father worked at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in various capacities from 1980-2002. 1) Always Put The Patient First Dad spent many family dinners on the phone with patients. While some might say he had poor boundaries, my Dad was always trying to help his patients.

He occasionally made house calls. His vivid expressions of humanity were reflected in how many of his patients swore by him—and the extra care and attention he gave them. My Dad stayed in touch with a few patients and their family members after he retired.

At his funeral, Jerry Buonanno, Sr. said of his wife, Connie: “Before she met your Dad, Connie was convinced she would never walk again because of her pain. Your Dad gave her the clinical help she needed—an intrathecal pain pump—and the confidence she could.

” When a Jain priest, Amrender Muniji, suffered a stroke and was languishing in a rehabilitation facility, Dad moved him to our home so he and my mother could nurse him back to health. My Dad’s primary identity was as a healer—and he always put the needs of his patients above all else. He never complained about burnout because he felt a deep sense of intrinsic reward from his work.

When a Jain religious figure, Muni Amrender ji, had a stroke, my Dad insisted he come home with him 2) Following his death, I reconnected with Barbara Viets, my Dad’s long-time assistant at Sloan-Kettering, who reminded me of a joke she used to tell my Dad. She said she used to tell him she wondered whether there was a sign with directions to his office at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport.

My Dad was a magnet for patients and medical trainees from all over the world (and especially our native India). He always said “yes” when people asked him for help. When I was young, I would ask my Dad why he always seemed to extend himself for others, sometimes at a clear cost to himself.

He would tell me simply, “If I don’t, who will?” I have never gotten over how much my Dad gave and gave—without any expectation of return. Dr. Vivek Murthy, the US Surgeon General, delivered the 10th Annual Subhash Jain Endowed Lecture at 3) Treat Pain With Intention My Dad’s primary area of clinical expertise was cancer pain management.

Dad was at the forefront of the movement to treat such pain with intentionality—believing strongly that, among cancer patients, pain was severely under-treated. As the epidemic of opiate addiction worsened—and hospitals and pharmacies became conservative about prescribing and dispensing pain medicines—he worried deeply that people who genuinely needed these medicines would not have access to them. He described these concerns in the .

“I’d be professing woeful ignorance were I not to acknowledge the medical profession’s complicity in the epidemic of opioid abuse in the United States,” he wrote. “But we are also key to the solution. We can’t retreat to and again be complicit in denying access to pain care to patients…who need our compassion and our care.

” Dad always worried that we might regress to where he started in the pain profession, where people in agony were inadequately treated. My Dad came to recognize the destructive potential of some pain medicines—but also worried about 4) Innovate With a View to the Basics My Dad joined the medical profession when new technologies and approaches were rapidly emerging. He loved trying new approaches to solve old problems.

Early in his career, he was among the first to use CT scans to precisely deliver nerve destroying medicines to specific pain-causing nerves. While he was excited to test and pilot these innovations, they were built on a foundation of knowledge of anatomy that was difficult to compete with. He would attribute a lot of his clinical successes to his strong foundations in basic and clinical science.

I always found his command of anatomy—a subject with which I struggled in medical school—to be inspirational, especially as he used this knowledge to drive results for patients. My Dad believed that dedicated healthcare professionals were at the heart of great medicine and 5) It’s All About the People My Dad came of age in the era of giants. His view was great healthcare was healthcare delivered by a true expert in the field.

In the era of protocols and systems-thinking, my Dad steadfastly believed that patients would do best in the hands of people with deep clinical expertise who were true masters of their craft. This is a view that has fallen out of favor as clinicians have increasingly been commoditized by larger and larger health systems. But it is something I have held dear as I have worked to build and scale the clinical companies of which I have been a part.

A clinician with deep expertise and heart will always be better for patients than patients treated in tightly managed, highly protocol-driven environments. Of course, this is a false dichotomy, but Dad believed that the highest value should always be placed on genuine expertise. As someone whose career began in the villages of Rajasthan, India, my father believed strongly in 6) Commit to Global Health Equity Not despite—but —he made evolved from a village doctor in India to a sub-specialist at a leading global cancer center, my Dad always felt a profound sense of obligation to rural populations in our native India.

He always wanted to level the playing field for others. He and his siblings started a hospital, school, and women’s empowerment center in rural Khichan, Phalodi tehsil. My Dad founded (IHBS) and contributed both funds and expertise to try to improve care for others, setting a powerful example for me and my brothers.

My brother Narpat, a dentist, has held dental camps in Khichan. My brother, Roopam, an entrepreneur, has been engaged in the administration of IHBS. And I have worked with DaVita Bridge of Life and Medical Missions for Children to bring kidney dialysis and cleft lip and palate surgery to the region.

My Dad’s attention was always focused on serving those who were less fortunate. While a trusting person by nature, my father was a firm believer that if something or someone seemed 7) If Someone or Something Seems Too Good to Be True, It Probably Is In the early part of my career, my Dad watched me get excited about lots of ideas to make healthcare better. And while he was always encouraging, he was occasionally skeptical.

I would come home from having been inspired by one thought-leader or another and he would (much to my chagrin) urge caution from drinking the Kool-Aid. Years later, as fads have come and gone—and truths have been revealed about people, motivations, and industry realities—I realize my Dad had wisdom about the healthcare industry that I didn’t fully appreciate when I was younger. Though he didn’t talk about them much, he had his own experiences with generations of thought-leaders, startups, and industry collaborations that didn’t really pan out.

As much as it sometimes annoyed me at the time, his healthy skepticism was grounding. My father felt strongly that physicians and other clinicians should lead healthcare organization. 8) Practicing Clinicians Should Lead Healthcare While he appreciated my work and career, my Dad had mixed feelings about me working in the administration of healthcare.

He felt that the growth of administration and policy in healthcare often added little to no value. Though he didn’t use these words, I believe he signaled early to me one of the primary causes for physician burnout: and excessively complex administration. He encouraged me to always maintain a footprint in taking care of patients no matter what I did.

After he retired, my Dad described a time earlier in his career when everyone in the hospital knew each other and it wasn’t difficult to get done what you needed to serve patients. With a growing web of internal and external regulations, people in healthcare began feeling . He spent the latter part of his career in a small office practice by himself because it felt it gave him the freedom and flexibility to take care of patients on his own terms.

He had a strong conviction that only people who take care of patients should lead healthcare—and that if they did, we would have a simpler, more operational system of care and insurance. My father believed strongly that self-respect was an important quality for physicians; in some way, 9) Respect Yourself Even When Others Don’t Respect You Dad experienced his share of racism in his time in healthcare. As an immigrant doctor with an unmistakable Indian accent, people under-estimated him from time to time.

He told me about an incident when he was teaching a small group session to medical students at Weill-Cornell Medical College (where he spent years on faculty) in the early 1980s. A snarky medical student perseverated meanly about not understanding what he was saying. My Dad—whose command of the English language was fine—was quick to put the student in his place.

He was fond of urging us to never put up with any hint of bias—and I had my Dad in my mind when I had a racist patient years later as a medical resident. My Dad always wanted us to operate with self-respect and always encouraged us to have pride in who we are and where we were from. At the peak of his life, my Dad was a compassionate physician and thought leader in the field of 10) Denial Isn’t Always Bad The final lesson I’ll share I learned by watching my Dad change from doctor to patient.

Toward the end of his life, my Dad suffered from multiple chronic illnesses. He took his medicines as prescribed, but he didn’t make ther lifestyle changes we often suggest to patients. He continued to live his life the way he wanted to live it.

As a family member, this was often frustrating. But, now that he is no longer with us, we take some solace in the fact that he never really lived his life as a sick person. That he left us with his dignity intact—living life on his own terms—is something healthcare professionals don’t always value as we devise treatment regimens.

I miss my Dad dearly. Among what I will miss most was his hard-fought wisdom—learned during a lifetime spent as a dedicated healer. I hope these lessons are as valuable to you as they have been to me.

.

From: forbes

URL: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sachinjain/2023/12/04/the-10-lessons-about-healthcare-i-learned-from-my-dad/