The autumn of 2013 was a stressful time for the Craten family, who live outside Phoenix, Arizona. In short order, three family members were diagnosed with the same type of salmonella infection. Salmonella is a foodborne bacteria that can travel on poultry meat and, as they would later find out, was sweeping the US in a nationwide outbreak .

All they knew at the time was that their 18-month-old son, Noah, was the sickest among the relatives: spiking daily fevers, losing the ability to walk straight, and developing a droop on one side of his face. Thanks to a CT scan, doctors discovered the infection had formed a rapidly growing abscess inside his brain. Emergency surgery saved his life, but pressure from the mass left lasting damage, affecting his speech and sensory processing and leaving him with learning disabilities.

Noah Craten is 10 now, a spunky kid who loves playing Minecraft and has an aide to help him through school. And his mother, Amanda, is an activist, a leader in a coalition of consumer groups that may just have compelled the biggest change in federal food-safety regulation in 20 years. Last week, responding to pressure from these groups, the US Department of Agriculture announced that it is considering reforms to the way it regulates the processing and sale of raw poultry, the largest single source of salmonella infections.

If the changes go through, they will give that agency the power to monitor salmonella contamination in live birds and slaughterhouses, and the power to force producers to recall contaminated meat from the marketplace. The agency doesn’t have those powers now, even though salmonella causes more serious illnesses than any other foodborne pathogen. It sickens about 1.

35 million people in the US each year; about 26,500 of them end up in the hospital, and 420 die. At its mildest, it causes fever and diarrhea that can last up to a week. But because it can migrate to the bloodstream and invade bones, joints, and the nervous system, it often leaves victims with arthritis and circulatory problems.

Today, the USDA can only ask meat producers to voluntarily recall their products, and companies don’t always move as rapidly as the agency would wish. That leaves consumers vulnerable to threats they do not know exist. “Noah got sick toward the end of an outbreak that lasted for 14 months,” Amanda Craten says.

“If there had been some sort of oversight, and there had been a recall early on, my son would not have gotten sick. ” The possible reforms were disclosed October 14 by the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service. They are contained in what the FSIS calls a “proposed framework,” the first steps in a process that might not be resolved until close to the 2024 election.

But if that process results in regulation, it will mark a permanent shift in US authority over food safety. “The exciting thing about this new proposal is that it’s going to apply to potentially all raw chicken products, which play a huge role in the number of cases of salmonellosis that we see,” says Sarah Sorscher, an attorney who is deputy director of regulatory affairs at the nonprofit Center for Science in the Public Interest, which has petitioned the USDA four times to declare the most dangerous strains adulterants and regulate them. “If we can bring the risk down in these products, we actually have a chance to bend the curve on foodborne illness.

” It might come as a surprise that the USDA didn’t already have this authority. But that agency (which regulates meat, poultry, and eggs; the US Food and Drug Administration oversees everything else) can force recalls only for contamination with one specific, small group of organisms: E. coli O157:H7 and a few related strains, which make toxins that destroy red blood cells.

It got that power during the shocked national reaction to a 1993 outbreak that sickened 732 kids who ate hamburgers from the Jack in the Box fast-food chain . That outbreak killed four and left 178 with kidney and brain damage. Salmonella comes from multiple sources: Small turtles sold in pet stores carry it, and so do the varieties of poultry that people keep as pets and backyard egg-layers.

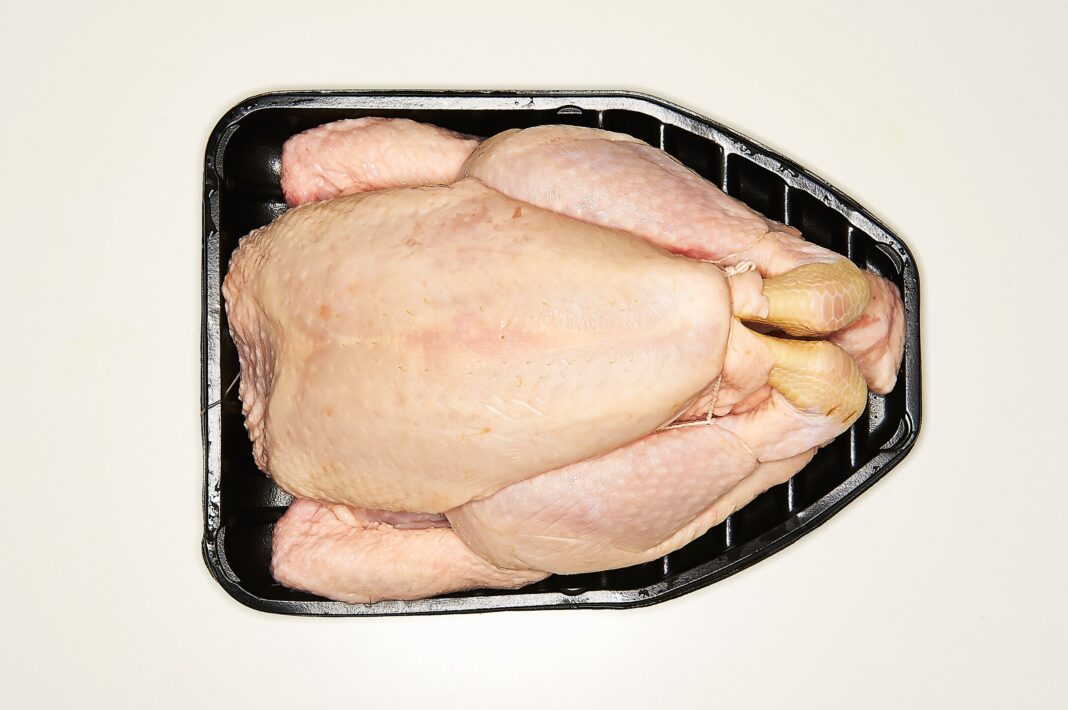

But at least one-fourth of the cases recognized in the US each year can reliably be traced back to eating commercially raised chicken. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that salmonella is present in one out of every 25 packages of chicken sold in US grocery stores. Strains linked to poultry are increasingly likely to be resistant to several common antibiotics , which are used to raise meat animals as well as in human medicine.

“One study has shown that poultry raised conventionally with antibiotics is twice as likely to contain multi-drug-resistant salmonella, compared to poultry raised without antibiotics,” says Matt Wellington, the public health campaigns director for the nonprofit US Public Interest Research Group. “And right now, it’s really up to consumers to try to navigate that, and that’s not fair. ” Just last week, US PIRG released a report that documented antibiotic use in the meat supply networks of US grocery chains, finding that suppliers for the companies’ private labels overwhelmingly still use antibiotics.

Salmonella is a tricky organism. There are thousands of strains, and only some cause serious illness. Many of them are common in poultry and can exist in birds’ guts without making them sick, which makes preventing them a low priority for bird growers.

The organisms also may be passed down between generations, from breeder birds to the ones that are raised for meat, which potentially implicates the entire production chain. Given all those complications, addressing contamination requires a comprehensive effort, regulating not just tainted meat but also slaughterhouse and farm conditions. The change in USDA leadership installed by the Biden administration may have summoned the political will to create it.

A year ago, the FSIS announced it would focus on salmonella and poultry, with the goal of cutting infections by 25 percent. The framework launched last week lays out the details of that commitment. It calls for testing flocks as they arrive at slaughterhouses, a goal that implies poultry growers would work to control the pathogen on their farms.

It proposes specific controls in slaughter and packaging beyond those that currently exist. And it advances the concept of an “enforceable final product standard,” which would consider the presence of salmonella, or certain strains of the pathogen, as reason to prevent meat from being sold. “We’re really pleased to see this, because it shows that FSIS has been listening to stakeholders, especially consumer advocacy groups,” says Mitzi D.

Baum, the CEO of the nonprofit Stop Foodborne Illness, which filed a citizens’ petition with the USDA last year asking it to create salmonella controls. (Stop Foodborne Illness, originally called Safe Tables Our Priority, was founded after the Jack in the Box outbreak; Amanda Craten is on its board . ) But it’s not only advocacy groups.

The effort is backed by four of the largest US poultry producers—Butterball, Perdue Farms, Tyson Foods, and Wayne Farms—which last year established a “coalition for poultry safety reform” with CSPI, Stop Foodborne Illness, Consumer Reports, and the Consumer Federation of America. Yet industry support is not universal. On the day the framework was announced, the National Chicken Council, the industry group for US poultry products, released a statement objecting to the move, saying the proposal “failed to use science and research.

” A public meeting on November 3 will launch the USDA’s formal process. But the real question is what happens after that. The framework commits the agency to producing an interim rule in 2023 and a final regulation in 2024.

That is extraordinarily fast by Washington, DC, standards. The short timeline may signal that the agency feels it needs to make real change—or realizes that change must happen before the 2024 election, if it is to occur at all. “My worry is that we’re going to take till 2023 to propose anything.

But then there’ll be the elections coming up, and you can’t do anything during the election. And then either the same administration, or a new administration, gets new people in,” says Bill Marler, a leading food safety lawyer who filed a USDA petition on salmonella in 2019 and represented one of the original E. coli victims in 1993.

But the consumer advocates who also have been pushing for this change hope the timeline will hold. “The thing that makes it most important for them to move quickly is that there are a million people getting sick from salmonella every year, and those people aren’t going to benefit until after this rule has been finalized,” Sorscher says. “It’s very important they move quickly because, yes, we don’t know what will happen in 2024—but also because Americans have already waited too long.

”.

From: wired

URL: https://www.wired.com/story/the-us-is-finally-considering-protections-against-salmonella/